The 1990s witnessed a significant transformation in cycling, propelling mountain biking from obscurity to mainstream popularity. The first mountain bike World Championships were held in Colorado in 1990, and by 1996, mountain biking was recognized as an Olympic sport. Delving into this era’s history has been incredibly enlightening, especially since my cycling journey began much later.

The Emergence of Gravel Bikes

Today, the cycling world is experiencing a similar revolution with the rise of gravel bikes. These bikes merge characteristics from road, touring, and mountain biking, creating a versatile but often misunderstood category. As gravel bikes continue to evolve, incorporating elements like flat bars and suspension, they are increasingly hard to categorize. They echo the versatility of the ’90s mountain bikes yet are designed for a distinct purpose.

What Sets Them Apart?

While a ’90s mountain bike can navigate gravel, it doesn’t make it a gravel bike. Conversely, modern gravel bikes can handle trails but aren’t true mountain bikes. This overlap leads to confusion, particularly as the definition of what a gravel bike is seems to continuously evolve. Are these changes driven by genuine innovation or merely marketing strategies to brand the “do-it-all” gravel bike? Regardless, the ongoing evolution is exciting for cycling enthusiasts.

Geometry Deep Dive: Then and Now

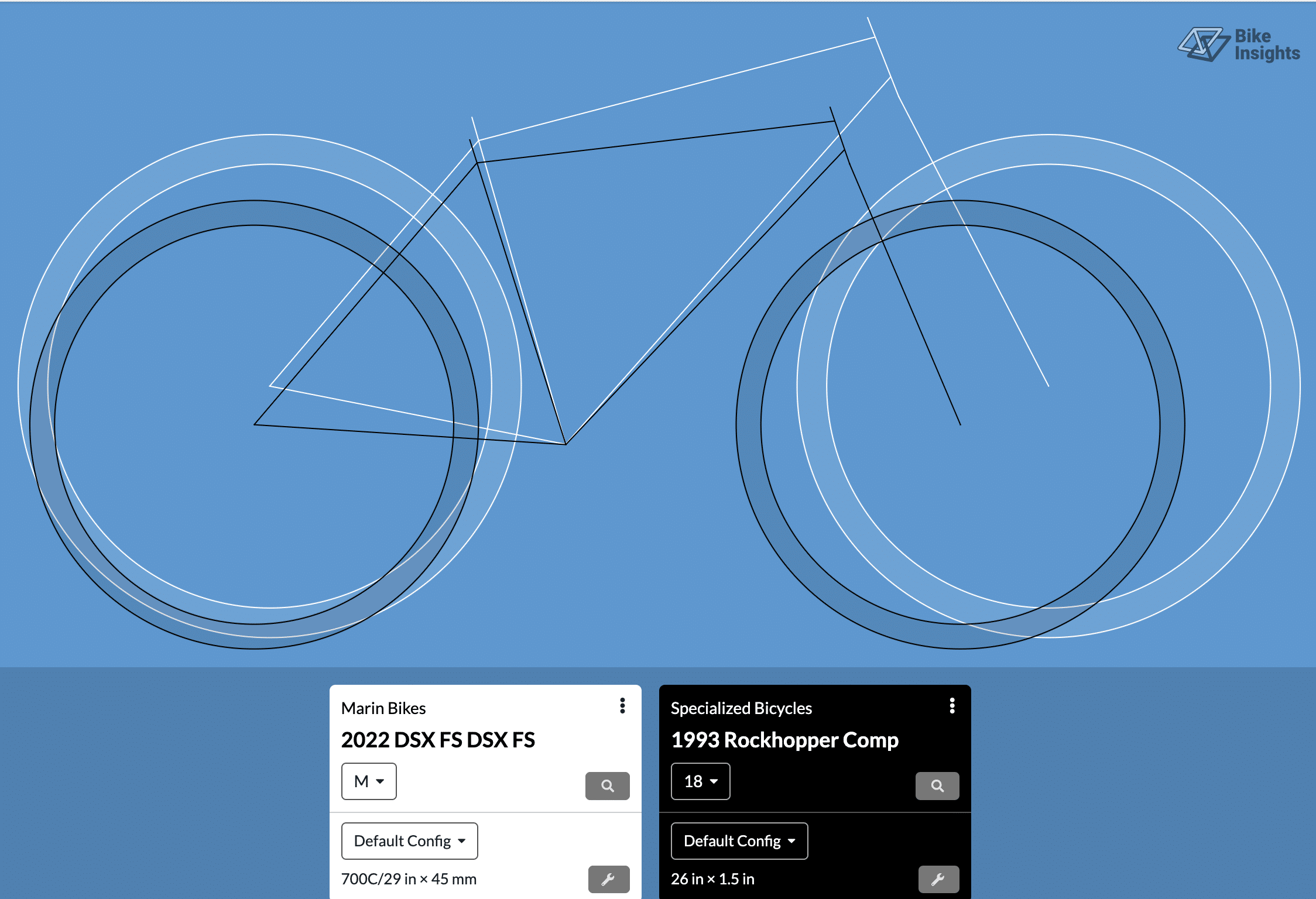

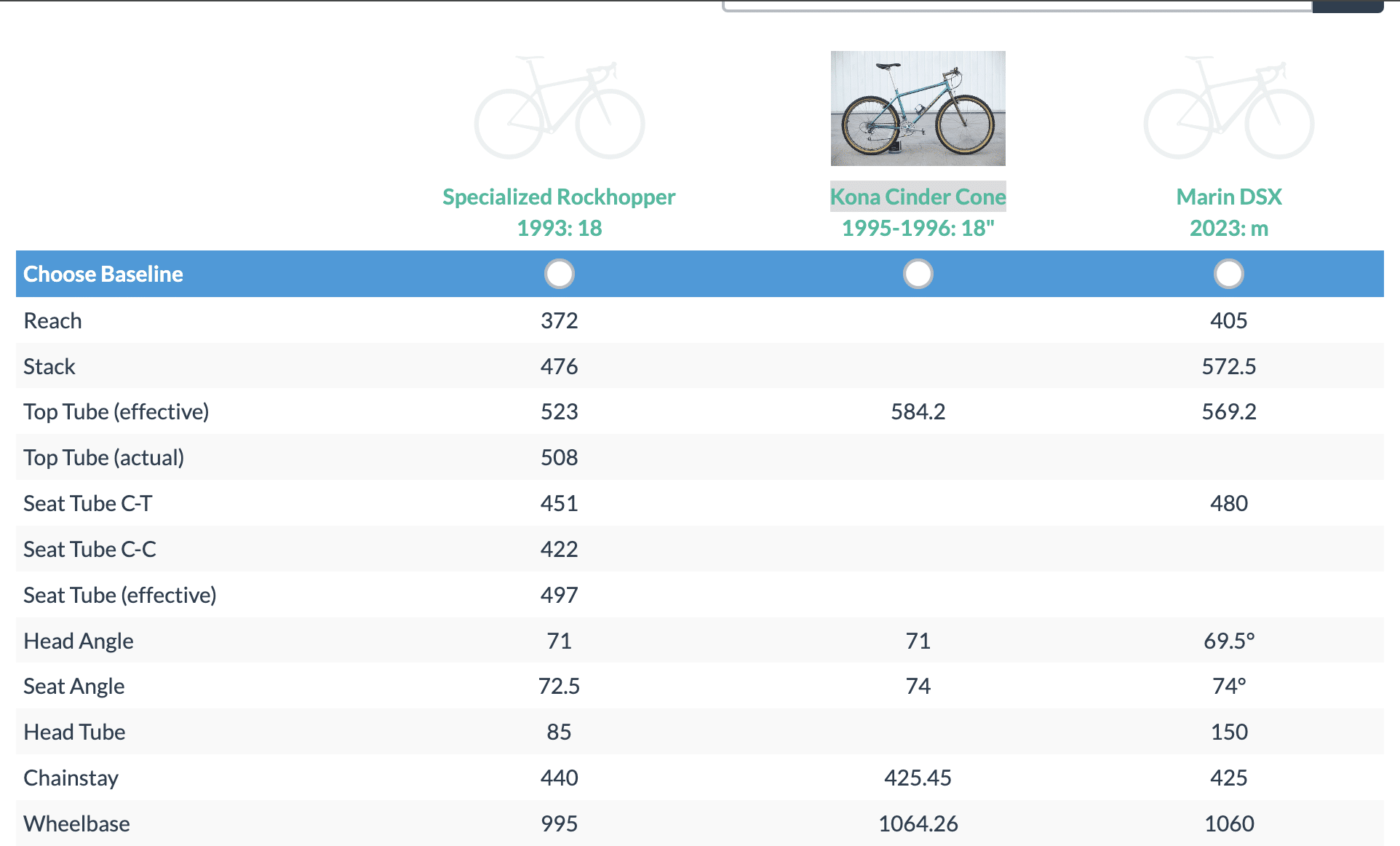

The geometry of ’90s mountain bikes like the Specialized Rockhopper vastly differs from today’s gravel bikes such as the Marin DSX FS. To illustrate, let’s compare their geometrical dimensions, showing the evolution from compact, agile mountain frames to the more balanced and stable designs of modern gravel bikes.

| Geometry Features | Marin DSX (Modern Gravel Bike) | Rockhopper (90s MTB) |

|---|---|---|

| Stack | 601.8mm | 476mm |

| Reach | 425mm | 372mm |

| Stack to Reach Ratio | 1.42:1 | 1.28:1 |

| Seat Tube Length, C-T | 480mm | 451mm |

| Top Tube Length, Effective/Horizontal Center | 597.6mm | — |

| Top Tube Length, Effective/Horizontal Unknown | — | 523mm |

| Top Tube Slope | 14.1 deg | 5.2 deg |

| Head Tube Angle | 68.5 deg | 71 deg |

| Seat Tube Angle | 74 deg | 72.5 deg |

| Head Tube Length | 120mm | 85mm |

| Bottom Bracket Drop | 82mm | 28mm |

| Bottom Bracket Height | 274mm | 289.6mm |

| Chainstay Length | 425mm | 440mm |

| Chainstay Length Horizontal | 417mm | 439.1mm |

| Front-Center | 685.2mm | 553mm |

| Front-Center Horizontal | 680.3mm | 555.9mm |

| Wheelbase | 1097.3mm | 995mm |

| Fork Offset/Rake | 47mm | 105mm |

| Fork Length, Unknown | — | 366mm |

| Trail | 89.7mm | 91.4mm |

| Mechanical Trail | 83.5mm | 85.1mm |

| Wheel Flop | 30.6mm | 31.1mm |

| Standover Height | 708mm | — |

| Tire to Pedal Spindle | 154.2mm 175 mm cranks | 65.4mm 170 mm cranks |

| Pedal Spindle to Ground Clearance | 99mm 175 mm cranks | 119.6mm 170 mm cranks |

The Marin DSX FS is often viewed as a “mountain biker’s gravel bike,” drawing significant similarities to mountain bikes from the ’90s, yet it is distinctly different. Here’s how it compares to the Specialized Rockhopper, a quintessential ’90s mountain bike, through detailed geometrical analysis:

- Stack and Reach: The Marin has a higher stack and slightly longer reach, promoting a more upright and comfortable riding position.

- Head Tube and Seat Tube Angles: The Marin’s angles are slightly slacker, providing stability and comfort over diverse terrains.

- Wheelbase and Chainstay Length: Longer in the Marin, these contribute to its stability and comfort on long rides.

An Early Precursor to Modern Gravel Bikes

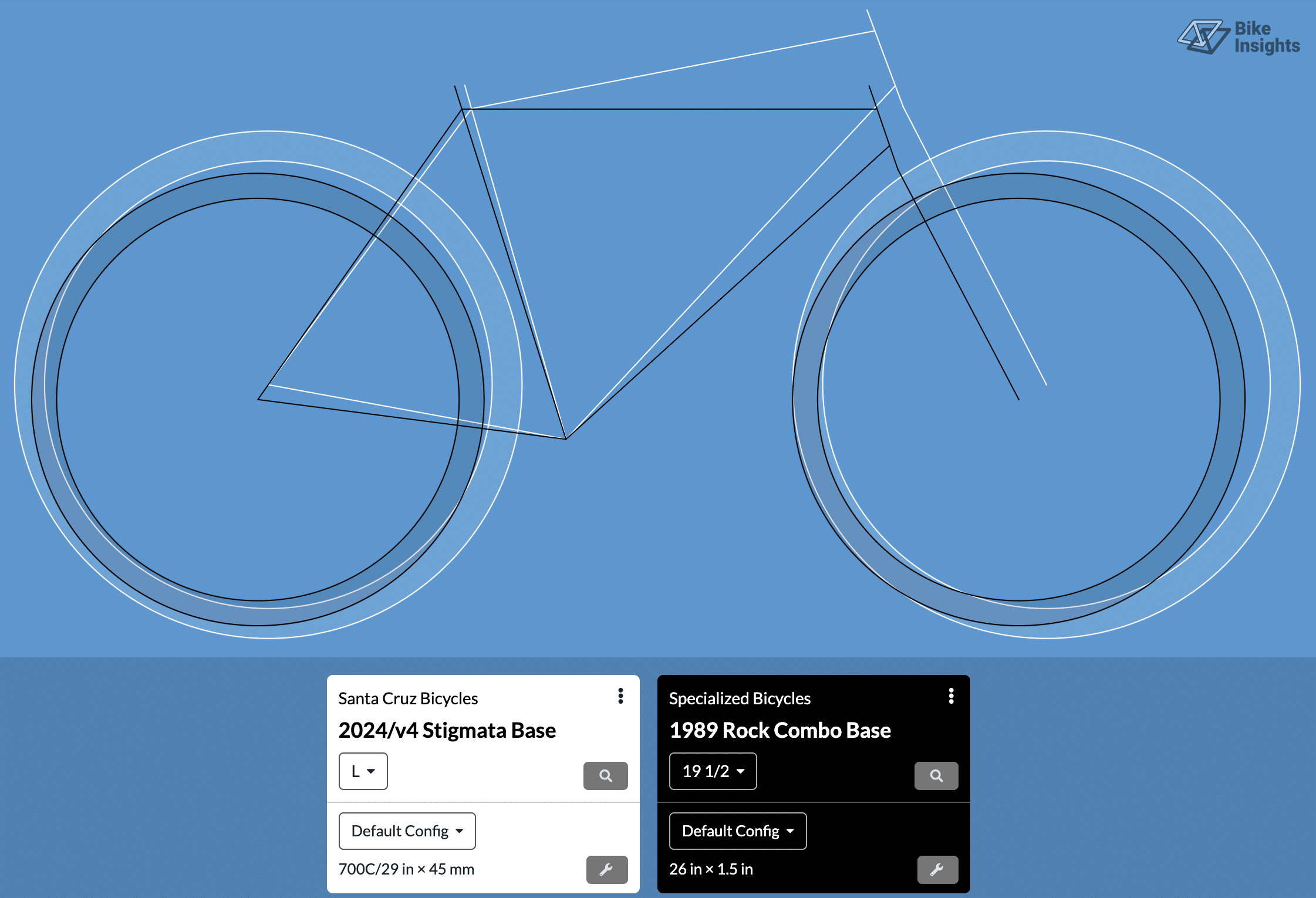

The Specialized Rock Combo might just stake a claim as the original gravel bike. Released long before the term “gravel bike” entered the cycling lexicon, the Rock Combo was a visionary design. With only 500 units produced, its rarity underscores its pioneering features which have since become mainstream in modern gravel bikes.

The Rock Combo was equipped with drop handlebars, 26-inch wheels, and a gearing system that was expansive compared to typical mountain bikes of its era. Its geometry leaned more towards road biking rather than mountain biking, making it exceptionally versatile for a variety of terrains.

To put the Rock Combo’s design in perspective, let’s compare it to a modern aggressive gravel bike like the Santa Cruz Stigmata. This comparison highlights how certain design elements have persisted and evolved over the decades.

| Geometry Features | Stigmata (Modern Gravel Bike) | Rock Combo (The Original Gravel Bike!) |

|---|---|---|

| Stack | 600mm | 494.4mm |

| Reach | 420mm | 423.2mm |

| Stack to Reach Ratio | 1.43:1 | 1.17:1 |

| Seat Tube Length, C-TTT | — | 498mm |

| Seat Tube Length, Unknown | 515mm | — |

| Top Tube Length, Effective/Horizontal Center | — | 580mm |

| Top Tube Length, Actual C-C | 592mm | 580mm |

| Top Tube Slope | 10.6deg | – |

| Head Tube Angle | 69.5deg | 71deg |

| Seat Tube Angle | 74deg | 72.5deg |

| Head Tube Length | 145mm | — |

| Bottom Bracket Drop | 76mm | 55.5mm |

| Bottom Bracket Height | 280mm | 262.1mm |

| Chainstay Length | 423mm | 434mm |

| Chainstay Length Horizontal | 416.1mm | 430.4mm |

| Front-Center | 668mm | 635mm |

| Front-Center Horizontal | 670.9mm | 632.6mm |

| Wheelbase | 1087mm | 1063mm |

| Fork Offset/Rake | 51.5mm | 43mm |

| Trail | 78.1mm high | 63.9mm mid/neutral |

| Mechanical Trail | 73.2mm | 60.4mm |

| Wheel Flop | 25.6mm | 19.7mm |

| Standover Height | 778mm | — |

| Tire to Pedal Spindle | 142mm 170 mm cranks | 147.4mm 170 mm cranks |

| Pedal Spindle to Ground Clearance | 110mm 170 mm cranks | 92.1mm 170 mm cranks |

The Rock Combo featured a more neutral or even downward sloping stem, a design choice that suggests a balance between aggressive handling and comfort over long distances. Notably, like many old school mountain bikes, it had longer chainstay lengths which provided stability at the rear, placing more weight over the front wheel for better control. This contrasts with the more balanced geometry distribution found in modern gravel bikes like the Santa Cruz Stigmata, which are designed to offer a comfortable ride over diverse terrains without compromising on responsiveness.

Though the Rock Combo was not labeled a gravel bike at the time, its design philosophy has clearly influenced the development of today’s gravel bikes. As we explore these early models, it becomes apparent that the foundations laid by bikes like the Rock Combo have helped shape the versatile, all-terrain bikes that we now recognize as essential gear for adventure cyclists.

This examination not only underscores the Rock Combo’s role in the evolution of bike design but also highlights how historical innovations continue to influence modern cycling trends. The journey from the Rock Combo to contemporary gravel bikes illustrates a significant evolution in cycling, where adaptability and versatility have become paramount.

While there are notable differences between gravel bikes and 1990s mountain bikes, the similarities in certain aspects cannot be ignored. This could be why many enthusiasts feel that modern gravel bikes are reminiscent of 1990s mountain bikes. However, they are distinctly different in key areas.

Performance and Handling

Gravel bikes and old school mountain bikes share a kinship in geometry and size, which influences their utility in various riding conditions. The older mountain bikes were designed for speed and agility with an aggressive setup that prioritized aerodynamic efficiency and snappy control. In contrast, modern gravel bikes, particularly those built for racing, offer a more comfortable and upright riding position which is conducive to long rides over mixed terrain.

The Evolution of Bicycle Designs

The development of drop bar setups on mountain bikes could have been an early solution, yet the industry moved towards more specialized designs. As the bicycle industry evolves, we see gravel bikes increasingly resembling what a cross-country mountain bike (XC MTB) used to be, incorporating elements like drop bars and suspension systems. This convergence has sparked a debate within the cycling community about the identity and classification of gravel bikes. Should they remain a hybrid between road and off-road bikes, akin to a two-wheeled SUV?

The Industry’s Response to Evolving Needs

The fragmentation within the bike categories, particularly around gravel bikes, is a topic of much discussion. Is the industry doing enough to define what exactly a gravel bike is? Should there be clearer distinctions and sub-categories like gravel adventure, gravel race, and gravel commute bikes? These questions highlight the need for clarity to prevent confusion and ensure that each bike type meets its intended use effectively.

Gearing Considerations

One critical area where gravel bikes often fall short is in their gearing. Many are marketed with the capability to “go anywhere,” yet they typically feature gearing suitable only for moderately challenging terrains, not the steep or rugged trails where more comprehensive gearing options are necessary. The limitation of 1x drivetrains becomes apparent here. For instance, while vintage mountain bikes like the RockHopper might offer a gear inch range from 21.21 to 98.34, modern gravel bikes might only offer a lower range starting around 23 inches, rarely reaching the lows needed for the most demanding terrains.

Case Study: The Kona Cinder Cone

Further analysis into old school mountain bikes brought the Kona Cinder Cone into focus. Comparing it with modern flat bar gravel bikes, such as the Marin DSX, shows that some older models have similar chainstay and wheelbase measurements, indicating comparable stability and handling characteristics. However, these comparisons only reveal part of the story. The geometry and specific design elements tailored to different riding experiences mean that while there are similarities, the bikes are built with different end uses in mind.

It’s crucial to understand that acknowledging the differences between 1990s mountain bikes and contemporary gravel bikes does not diminish the value or enjoyment one might find in the older models. In fact, the cycling community continues to celebrate and utilize vintage mountain bikes through numerous retrofits and conversions into gravel and bikepacking setups. This trend underscores the versatility and enduring appeal of these bikes. However, equating them directly with today’s gravel bikes oversimplifies the significant advancements that have been made in bike engineering.

The distinction in geometry, which often influences riding comfort and efficiency, is particularly notable. These differences can significantly impact the riding experience, positively or negatively, depending on what the rider needs from their bike. For example, while the Kona Cinder Cone may mirror some modern gravel bikes in certain specs, it represents a specific point in the broader evolution from traditional mountain bikes to the gravel bikes we see today.

Modern gravel bikes are not merely updated versions of old mountain bikes; they are a refined evolution, designed to meet the demands of today’s riders. They enhance the experiences that old mountain bikes were initially sought for, such as improved handling, comfort, and versatility across varied terrains. Notable developments in this area include bikes like the Specialized Rock Combo and Canyon’s Grizl CF SL 7 Throwback, which blend historical influences with contemporary advancements.

These bikes strive to fulfill the demands that their mountain biking predecessors were built for, but with superior technology and design that enhance their performance and usability. As the gravel bike category continues to expand, these bikes offer greater ease of use, more refined ergonomics, and efficiencies that far surpass those of the 1990s mountain bikes. In this way, the journey of the gravel bike is a testament to the cycling industry’s commitment to innovation and rider satisfaction, ensuring that each new generation of bikes offers a more refined and enjoyable riding experience.